Search the Community

Showing results for tags 'tardive dyskinesia'.

-

Freeby60: this month is the 24th anniversary of getting on ADs - 24 years!

Freeby60 posted a topic in Introductions and updates

Hello- as my topic title shows, I have been on anti-depressants for 24 years (20mgs Lexepro, 175 mgs Wellbutrin). It is hard to face. After the birth of my first son, I began having acute anxiety. When I told my gynecologist he told me it was common after giving birth because of hormonal changes. In such cases, he recommends about six months of medication to help with the symptoms and recommended a psychiatrist that he works with for patients such as me. I'm sure none of you are surprised to know that, as is all too common, I never got off the drugs for very long. Each time withdrawel symptoms were interpreted as my illness returning. My mother suffered from anxiety and depression all her sad life, so it wasn't hard to believe that I was ill. Yet, I still tried a few times to stop the drugs. Interestingly, once it became clear how difficult it was to get off the drugs, I knew with certainty that I needed to stop taking them. I Thought I would put if off until I was retired, so I would have less stress, etc. to deal with the WD, but when I learned about the10% taper it gave me hope that I can be AD free by my 60th birthday! I will start with the Lexepro. Getting myself a scale and using a spreadsheet to calculate the decreases. I'm getting my yoga and walking on, and continuing meditation for success! I'm so glad to have this site for reference, information and support!- 469 replies

-

- long-term ad use

- escitalopram

-

(and 4 more)

Tagged with:

-

Hi all, my story is so very long but the short story is i was on zoloft 50 mg for 15 years (only drug i was ever on). I tried multiple times to get off but would get severe discontinuation syndrome each time so i thought i just had to stay on it for life. I will go into those symptoms if you ask. Anyways about 4 years ago i developed benign fasiculations and resting tremor. It took seeing multiple docs and finally a second neurologist and he said this is common with zoloft. So i had to get off it but i was scared to death because of the severe discontinuation that i would compare to heroin withdrawal. So i was so scared i never went back to the doctor and thought maybe i can live with BFS and the tremor. But then my neurological symptoms got worse and led to parkinsons which was drug induced and dyskinesia. The facial grimacing was way more annoying than the fasiculations and it affected my blood pressure too, thats how parkinsons works, it affects the autonomic system so i had bad orthostatic hypotension and that was dibilitating but somehow i pushed through. I had many more issues, if you ask i can write about them. Anyways this time i was ready to get off zoloft so i go to the doctor and he says "wow you've been on it for 15 years" and i thought "WOW you idiot. Your office is the one who has been prescribing this to me all these years". They never once told me to make an appt if i hadnt been there in a few years, they just kept refilling it. They should require patients to have biyearly appts and check them for neurological signs and if the patient doesnt make an appt than they should not get a refill. I am very mad at my poor healthcare and management (total lack thereof) but again my story is so long i can write it if you ask. Anyways my doc said to wean off over like 2 months. That was too fast so i did it on my on and weaned off 50 mg over a 6 month period and for the first time i did not get discontinuation syndrome! I was scared to death but i did it and was shocked i did not get discontinuation. Weaning that slow is the answer. I only had some mild things like some mood swings, swollen lymph nodes which always happens when i wean off for some reason, headaches, i can go into detail if you ask. My neurological disorders are also going away. I am 20 days off zoloft and feel great and i would say my neurological issues are like 80% better and i hope to recover completely with time (i might have permanent damage). Anyways i am posting because i am very angry at the healthcare community for their lack of knowledge on how zoloft, though rare, does cause dyskinesia, BFS, and parkinsonism. Docs do not seem to know to look for these signs and put a stop to it before irreversible damage occurs which is a disability. They are too freely handing out these meds to your average person with basic stress that can actually manage without meds like seeking CBT, meditation, yoga, qigong, etc. i am one of those type of people. Patients are never checked up on on these meds. I know personally from working in gastroenterology for years that almost everyone is on anxiety or antidepressants and that to me is a crime because every single one of them are having unexplained problems with a lot of expensive negative testing and they are frustrated but no one is relaying it is the medication causing it and how imperitive it is to get off it. I am against all these meds (unless the patient has true mental disorder like bipolar or is in a stage of suicidal ideation etc). I am just very angry. For me, to address that, i want and need to raise awareness but i feel no one would believe my story because it is so rare but i think more common than we know because it is being unreported and doctors dont know enough to spot tardive dyskinesia etc so it takes years. Anyone else with a story like mine?

- 111 replies

-

2

-

- tardive dyskinesia

- parkinsonism

-

(and 4 more)

Tagged with:

-

Hi, all-- I am so grateful to have found this site. It is helpful to know that I'm not alone. This is my first post, I will try my best to be succinct. I'm a 42 y/o female. I've been on Zoloft for 12 years, anywhere from 50mg daily to 175mg. I'd say my average over the years is probably around 125mg daily. My signature has a breakdown of my history. I've also taken klonopin during this time, but I take it PRN as I have never agreed with the doc suggestions to take this med multiple times daily. So in terms of my average klonopin dosing, during acute anxiety or hospitalization I take it multiple times daily but otherwise I take it maybe once or twice a month (more or less). My pills are 0.5, but I have a sensitive system so I take one quarter of that or maybe a half. A full pill usually means I am heading into a major depressive episode or something pretty difficult is going on. I smoked marijuana for about 7 years, but had to stop that in July 2020 due to cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS). Lastly, I began a magnesium supplement around July 2020, and it has greatly helped with daily anxiety. The difference has been pronounced for me. For the past five/six years or so, I noticed that I occasionally got facial tics when I wake up in the morning. They were small, brief, and random, usually my jaw jiggling or shutting, or my eyes shutting closed due to my cheeks lifting. I thought it might be the Zoloft, but I didn't look into it too much. Well, now I've looked into it and I'm terrified. For the past 6 months, I'd say, the tics have started to happen during the course of the day and not just when I wake up in the morning. A couple of days ago, I was lying in bed and my throat/esophagus just started twitching up and down a few times-- that one was scary. I have an HMO, so I am in the process of seeking out a holistic psychiatrist on my own. I've seen the list on this site, that's been very helpful! I have a few questions for anyone that can help: In your experience, is it okay to have a long-distance psych? Does it make a difference? I'd rather see someone who knows what they're doing and is far, far away than someone close by who doesn't know or believe in patient-centered care. How might this hamper care? Do the TD symptoms indicate that I should follow a quicker taper? Or is this a matter of doing the 10% and then waiting/hoping that TD symptoms don't get worse? Can klonopin cause TD? I haven't seen anything about this, but I'd love to hear others' experiences. I will ask my psych the same thing, but are there any supplements that folks here recommend to help with the taper? I've tried tapering once before back in 2011-2013 (I thought I was tapering slowly, but given the info we have now I can see I was most definitely not going slowly. I was also following bad advice about taking my SSRI "every other day" to even out the amount of med in my bloodstream), and had what I now recognize to be an acute and quickly-manifesting depressive episode as a result of withdrawal. I understand that everyone's body is different, but any experiences with supplements is very welcome. Of course I am impatient to get off of this drug which could now be causing me a lot of harm. I have done loads and loads of work with therapists on my PTSD and depression, but the Zoloft did help me with that at the beginning, very much. I have so many conflicting feelings, but fear overrides them all because I would very much love to retain my ability to swallow and chew voluntarily (the cosmetic fears are also there, but to a lesser degree). I am a Buddhist and humanist and practice daily in one way or another, but as I'm sure many of us know a strong depression can and will obliterate reason, faith, belief, you name it. Thankfully I have a wife who shares my beliefs, and she is a rock. Thank you so much for any help. I am terrified of this journey, but I am very heartened that at least I have others to share it with.

- 26 replies

-

- tardive dyskinesia

- zoloft

-

(and 3 more)

Tagged with:

-

Recently my psychiatrist upped Abilify to the max dose 30mg. I am also taking Celexa 40 mg. Have been taking psychiatric drugs for 10 years now. Have tried to withdrawal by myself in the past and schizoaffective symptoms come back worse. Now I am scared of taking the drugs because my tongue keeps moving back and forth in my mouth, and I am afraid of making it worse. Can I just stop the medications and when I start experiencing withdrawal symptoms, just take a smallest dose possible to alleviate the withdrawal symptoms, as I wean off them? I have a family history with lots of schizophrenia, and it seemed to help with somewhat, and people said I seem better on them. But now want to try to go off and try alternative therapies/natural diets.

- 12 replies

-

- citalopram

- Celexa

-

(and 3 more)

Tagged with:

-

Depression. Got prescribed Citalopram and Delorazepam in medium doses. After several months nothing changed. Doctors escalated, introduced Zyprexa (5mg) (note: never had psychotic symptoms). I was "treatment resistant", so they added Lithium (I never exceeded the toxic dosage). Been going like that for about 2 years. No progress whatsoever with the psychiatrist. I developed a network of friends and started studying all the philosophy and self-help I could. I felt stronger. I didn't trust the psychiatrist for a lot of evident reasons, including the fact that she wanted me to keep taking AP life-long, so I fired him/her. For seven months then I was quite fine. I was much more impulsive and reckless in many aspects but I started to work again with success and I started excercising, losing a lot of weight and building my muscles and confidence up. Something "legal" happened, I had to be sent to a recovery structure. For a month I was put on 20mg Aripiprazole daily. Developed psychosis for the first time in my life. That really scared me. I was put on Delorazepam, Clotiapine, Valproate and 75mg Lurasidone daily. I was in that place for two years (can't remember the exact doses). Worked with another psychiatrist when I got out. Started from 6mg Invega and 2mg Alprazolam to 1.5mg Invega and keeping the benzodiazepine at the same level. Gained tons of weight, blood levels got completely destroyed (tryglicerids, cholesterol, sugars). I also developed "slipping hands" - parkinsonism like symptoms, numbed feelings, difficulties concentrating, low energy, extreme impulsive behaviour and letargia. Had to move to another city to start a new job - which I have training for - but I couldn't hold it due to the aforementioned parkinsonism effects (it was a precision work), social anxiety and stress vulnerability. Currently went back to 3mg AP and 2mg Alprazolam. The dose is way lower than what I used to take but probably due to the long exposure to those chemicals I find impossible to skip the daily dose. I try to be as positive as possible but the situation is quite dire - suffered hard for the stigma from friends and family and I find myself relying on somebody's else resources to keep on living. I'm here to try to taper and get advices. I can afford an appropriate weight scale and I know how to make % and proportions, even solutions, but I noticed when I took the split 1.5mg of AP pill that energy levels, mood and withdrawal symptoms weren't as manageable as with the complete pill. Should I go with the orthodox 10% monthly reduction dosage? What would be better to scale off first? The AP of the benzo? Sorry if I may seem a little blunt, I don't mean to, but I really need help to get things back on track and no professional seems to be eager in doing that. Thanks for any answer in advance.

-

This may be short, as I just took my evening Clonazepam dose which seems to be the only thing that relaxes my neck muscles (eventually) so that I can stay asleep. It often takes effect by giving me thirty or so seconds of warning that I am about to drop off. So I apologize if I accidentally post gibberish; I don't always get enough notice to put the iThingy down and the random key presses that result might post or just erase all my hard work. But I found this website this evening: Dystonia Medical Research Foundation I wanted to share it because it is a very useful resource so far as I have made use of it. But also because reading the info there seems revelatory and I am too hyper to go to sleep without shouting from some rooftop or another first. I could go into great detail--and I might--but in essence the descriptions of many of the typical symptoms of secondary/tardive dystonia are reading like the solution to this giant puzzle I have been trying to solve for a year and a half and I am at once relieved and angered by the possibility that this could be what is going on with my face, eyes, jaw, neck, shoulders, and the occasional twitchy muscle lower to the ground than chest level. Jaw wants to clamp shut day and night: yes that could be dystonia! Eyes sensitive to light when eye and other muscles freaking out: yes that could be dystonia! Painful spasms that follow cyclical but still unpredictable patterns almost exclusively from the neck up: yes! That could be... Etc. Oh and the Inexplicable fatigue: involuntary muscle contractions are just as energy intensive as voluntary ones. Dystonia may make me feel as though I were working out 18-24 hours a day every single day! It would even explain my voracious appetite for protein, which is much like it was when I did work out regularly. The nausea that interferes with my current efforts to stay fed is still a mystery I guess, although I do want to investigate any relation between constant muscle activity and dehydration since it gets worse if I am without water for long and that aggravates any nausea trying to crop up at the time. The question nobody can answer is why a psychiatrist who took his patient off olanzapine after more than twelve years because that patient was beginning to twitch in a Tardive Dyskinesia sort of way would continue to insist that muscle spasms, pain, and fatigue that have not remitted since the drug was discontinued were "not the Zyprexa". I will concede that I may be fixated on this single etiology to the exclusion of other possibilities, but I still find it appalling that he suggested I get checked for mono when I mentioned fatigue (again) this last time around. So anyway. Please bear with the enthusiasm; it is true that there is no cure for tardive dystonia, but for once in what seems like a lifetime of trying to claim appropriate names for myself, I am very keen to find out if this is indeed a socially-recognizable one for the bulk of what currently ails me. I am vacationing in Seattle right now, but will be looking for a neurologist and/or movement disorder specialist when I return to San Francisco. In the meantime I will text this and a few other links to my MD and my therapist to see if they see me in these symptoms as well as I do. I am also going to take my shiny new Medicare card and go shopping for a different psychiatrist. Tardive Dystonia. I understand why I had never heard if it, but prescribing neuroleptics without having heard of it? I know: the propaganda is no respecter of educative rank, but it took only two google searches as to the current knowledge of tardive dyskinesia for me to come across it. Ok I think I might be sleepy enough to ignore the perpetual shrug that my shoulders find themselves fixed in. I hope that the link is helpful to someone else too.

- 44 replies

-

- Antipsychotic

- Tardive dyskinesia

- (and 2 more)

-

Hello everyone, my name is Nicholas and I'm a 21 years old guy from Italy. I suffered from chronic insomnia from the age of 15 and in mid-February 2017 was prescribed before bedtime the antidepressant mirtazapine at 15 mg and the antipsychotic olanzapine at 2,5 mg. I took them for 2 weeks without improvement. Therefore the psychiatrist increased mirtazapine at 30 mg and olanzapine at 10 mg. Now I believe that he thought I had bipolar disorder type 1 but I hadn’t any mental illnes. I took olanzapine at 10 mg because I think was only a tranquilizer and because I trusted the doctor. Olanzapine made me sleep for 13 hours but I was no longer myself. After 5 days I tried to split the tablet but it gave me a strange effect. So I continued for others 15 days at 10 mg because I really needed to sleep. Then in April 2017 I tapered olanzapine in 1 week because I could not live anymore like that. I took it for a total of 48 days. After this I reduced mirtazapine to 15 mg and 1 week later I stop cold turkey. At that time I took the benzodiazepine brotizolam at 0,25 mg for 2 weeks to help me sleep. The withdrawal symptoms were terrible for 4 months and I have not been the same anymore. When I was on mirtazapine and olanzapine I had eyelids fasciculation 2 or 3 times per day. When I quitted olanzapine the eyelids fasciculation ceased. 2 weeks after withdrawal from olanzapine and 1 week from mirtazapine I started to have frequently intermittent muscle twitching in the left thigh and occasionaly pulsating muscles in other parts of the body. After less than a couple of months they have decreased in frequency and intensity but didn’t stop completely. During this period I was forced to take the antidepressant sertraline and the benzodiazepine diazepam because for the new psychiatrist I had obsessive compulsive disorder with an obsession for the damage of antipsychotics. I did not have anything like that and could taper and withdraw after 3 months in July 2017. Now I think maybe that the muscles twitching have diminished because diazepam is also a muscle relaxant. In August 2017 I started to have continuous fasciculations in the legs when I lie down and less frequently when I sit while I never had them when I move. Few times a day I had pulsating muscles also in the arms and the trunc but never in the face. I never had muscle twitches in multiple parts of the body at the same time. In September the muscles twitching moved for 1 week in the lower abdominals. In October 2017 for 2 weeks the muscles twitches suddenly stopped in the legs and continued in the rest of the body about 10 times per day. When the muscles twitching returned they were milder. Sometimes the fasciculations are so mild that when I looked at my calf I saw them without feel them. In the legs they have become more single rapid muscular contractions than pulsating muscles. Soon after I started to have continuos pulsating muscle in my upper lip. The muscle twitch was very mild and lasted 2 weeks but after it I have sometimes pulsating muscle also in my face. Do you think it is a tardive dyskinesia caused by olanzapine despite I haven’t involuntary body movements? Do you think it could be some other side effect caused by olanzapine or maybe mirtazapine? It’s 8 months that I’ve it. I have been visited by several psychiatrists and neurologists and everyone said it was just stress. Even if I do not have the symptoms of tardive dyskinesia I do not know what else it could be: I’m not stressed and I do not suffer from anxiety, I do not take stimulants, I can sleep, I have had blood tests and I haven’t electrolyte imbalances or hypoglycemia, I did electromyography and had normal results. The thing that worries me most is that there is a very large amount of medical literature that associates tardive dyskinesia with cognitive impairments. If it were to be tardive dyskinesia do you think that the fact that for almost 2 weeks the muscles twitches had almost disappeared means that I am healing? Thank you and greetings from Italy.

Hello everyone, my name is Nicholas and I'm a 21 years old guy from Italy. I suffered from chronic insomnia from the age of 15 and in mid-February 2017 was prescribed before bedtime the antidepressant mirtazapine at 15 mg and the antipsychotic olanzapine at 2,5 mg. I took them for 2 weeks without improvement. Therefore the psychiatrist increased mirtazapine at 30 mg and olanzapine at 10 mg. Now I believe that he thought I had bipolar disorder type 1 but I hadn’t any mental illnes. I took olanzapine at 10 mg because I think was only a tranquilizer and because I trusted the doctor. Olanzapine made me sleep for 13 hours but I was no longer myself. After 5 days I tried to split the tablet but it gave me a strange effect. So I continued for others 15 days at 10 mg because I really needed to sleep. Then in April 2017 I tapered olanzapine in 1 week because I could not live anymore like that. I took it for a total of 48 days. After this I reduced mirtazapine to 15 mg and 1 week later I stop cold turkey. At that time I took the benzodiazepine brotizolam at 0,25 mg for 2 weeks to help me sleep. The withdrawal symptoms were terrible for 4 months and I have not been the same anymore. When I was on mirtazapine and olanzapine I had eyelids fasciculation 2 or 3 times per day. When I quitted olanzapine the eyelids fasciculation ceased. 2 weeks after withdrawal from olanzapine and 1 week from mirtazapine I started to have frequently intermittent muscle twitching in the left thigh and occasionaly pulsating muscles in other parts of the body. After less than a couple of months they have decreased in frequency and intensity but didn’t stop completely. During this period I was forced to take the antidepressant sertraline and the benzodiazepine diazepam because for the new psychiatrist I had obsessive compulsive disorder with an obsession for the damage of antipsychotics. I did not have anything like that and could taper and withdraw after 3 months in July 2017. Now I think maybe that the muscles twitching have diminished because diazepam is also a muscle relaxant. In August 2017 I started to have continuous fasciculations in the legs when I lie down and less frequently when I sit while I never had them when I move. Few times a day I had pulsating muscles also in the arms and the trunc but never in the face. I never had muscle twitches in multiple parts of the body at the same time. In September the muscles twitching moved for 1 week in the lower abdominals. In October 2017 for 2 weeks the muscles twitches suddenly stopped in the legs and continued in the rest of the body about 10 times per day. When the muscles twitching returned they were milder. Sometimes the fasciculations are so mild that when I looked at my calf I saw them without feel them. In the legs they have become more single rapid muscular contractions than pulsating muscles. Soon after I started to have continuos pulsating muscle in my upper lip. The muscle twitch was very mild and lasted 2 weeks but after it I have sometimes pulsating muscle also in my face. Do you think it is a tardive dyskinesia caused by olanzapine despite I haven’t involuntary body movements? Do you think it could be some other side effect caused by olanzapine or maybe mirtazapine? It’s 8 months that I’ve it. I have been visited by several psychiatrists and neurologists and everyone said it was just stress. Even if I do not have the symptoms of tardive dyskinesia I do not know what else it could be: I’m not stressed and I do not suffer from anxiety, I do not take stimulants, I can sleep, I have had blood tests and I haven’t electrolyte imbalances or hypoglycemia, I did electromyography and had normal results. The thing that worries me most is that there is a very large amount of medical literature that associates tardive dyskinesia with cognitive impairments. If it were to be tardive dyskinesia do you think that the fact that for almost 2 weeks the muscles twitches had almost disappeared means that I am healing? Thank you and greetings from Italy.- 14 replies

-

- olanzapine

- zyprexa

-

(and 4 more)

Tagged with:

-

Chouinard, 2017 Antipsychotic-Induced Dopamine Supersensitivity Psychosis: Pharmacology, Criteria, and Therapy

DoctorMussyWasHere posted a topic in From journals and scientific sources

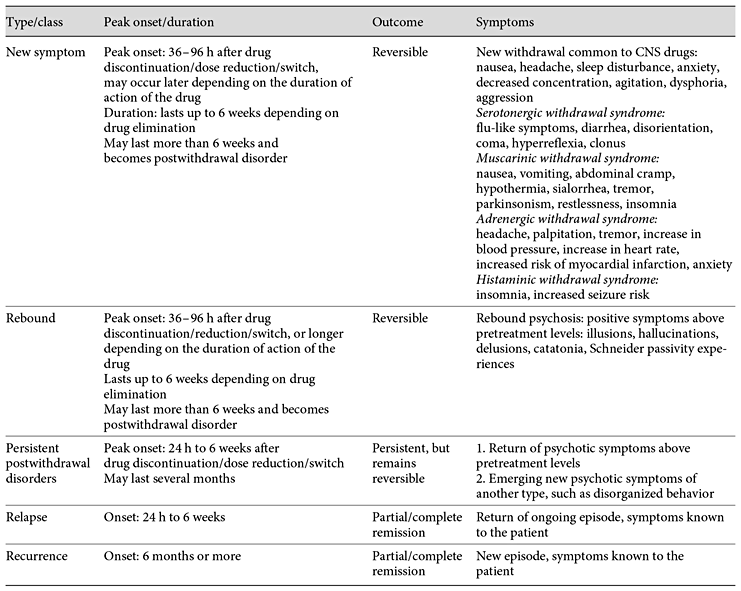

This paper is one of the most thorough I have come across in relation to its topic: Supersensitivity Psychosis, the reason antipsychotics are in fact pro-psychotics. Antipsychotic-Induced Dopamine Supersensitivity Psychosis: Pharmacology, Criteria, and Therapy Chouinard G.a,b,g · Samaha A.-N.c, d · Chouinard V.-A.e, f · Peretti C.-S.g · Kanahara N.h · Takase M.i· Iyo M.h, i It's long and thorough - over an hour at 200wds/pm The lead author, Guy Chouinard, is notable for his role in identifying this phenomenon in 1978. This blog post has a little more background on Chouinard. Although the content may be a little on the technical side, which is say more of interest to laboratory researchers, the paper proposes diagnostic guidelines. Whether or not these will make it into future manuals such as the DSM and ICD remains to be seen, however it would be interesting to see how this would sit alongside modern descriptions of disorders, many of which have absorbed the side effects of medications into their lists of symptoms, thereby masking them, and leading to ever-increasing doses. I think the descriptions of what is drug-induced versus what is a latent problem may potentially be useful. The fact that it recognises a distinction and attempts to define it at all is fairly noteworthy. I've included that section, preceded by the abstract, and links to the original content. This comes to around 6000 words - about 30 minutes reading. Abstract The first-line treatment for psychotic disorders remains antipsychotic drugs with receptor antagonist properties at D2-like dopamine receptors. However, long-term administration of antipsychotics can upregulate D2 receptors and produce receptor supersensitivity manifested by behavioral supersensitivity to dopamine stimulation in animals, and movement disorders and supersensitivity psychosis (SP) in patients. Antipsychotic-induced SP was first described as the emergence of psychotic symptoms with tardive dyskinesia (TD) and a fall in prolactin levels following drug discontinuation. In the era of first-generation antipsychotics, 4 clinical features characterized drug-induced SP: rapid relapse after drug discontinuation/dose reduction/switch of antipsychotics, tolerance to previously observed therapeutic effects, co-occurring TD, and psychotic exacerbation by life stressors. We review 3 recent studies on the prevalence rates of SP, and the link to treatment resistance and psychotic relapse in the era of second-generation antipsychotics (risperidone, paliperidone, perospirone, and long-acting injectable risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, and aripiprazole). These studies show that the prevalence rates of SP remain high in schizophrenia (30%) and higher (70%) in treatment-resistant schizophrenia. We then present neurobehavioral findings on antipsychotic-induced supersensitivity to dopamine from animal studies. Next, we propose criteria for SP, which describe psychotic symptoms and co-occurring movement disorders more precisely. Detection of mild/borderline drug-induced movement disorders permits early recognition of overblockade of D2 receptors, responsible for SP and TD. Finally, we describe 3 antipsychotic withdrawal syndromes, similar to those seen with other CNS drugs, and we propose approaches to treat, potentially prevent, or temporarily manage SP. Introduction Pharmacological Mechanisms by Which Antipsychotics Potentially Increase D2 Receptor Density and/or Function Clinical Characteristics and Consequences of SP in the Era of SGAs Evolving Conceptual Framework of Antipsychotic-Induced Dopamine SP in Line with Other CNS Drug Withdrawal Syndromes Pharmacological Link between a Compensatory Increase in D2/D2High Receptor Density and SP Guidelines for SP and TD Prevention Choice of the Antipsychotic Guidelines for SP Treatment Guidelines for the Management of Antipsychotic Withdrawal Evolving Conceptual Framework of Antipsychotic-Induced Dopamine SP in Line with Other CNS Drug Withdrawal Syndromes Classification of Antipsychotic Withdrawal Syndromes Based on ongoing research into SP characteristics, along with evidence for withdrawal symptoms found with other CNS drug classes, we present a conceptual framework [1,41] for identifying SP and other antipsychotic withdrawal syndromes (Tables 1, 2). Chouinard and colleagues [1,31,89,90] reported 3 types of withdrawal syndromes associated with CNS drugs, including opiates, barbiturates, and alcohol: (1) new or classical withdrawal symptoms; (2) rebound; and (3) postwithdrawal disorders (Table 1). These 3 types of withdrawal syndromes need to be differentiated from relapse and recurrence of the original illness. Relapse is defined as the gradual return to symptoms seen before treatment and entails a return of the ongoing episode, while recurrence is defined as a new episode of the illness (Table 1). Table 1 Type of antipsychotic withdrawal compared to relapse and recurrence [41] Table 2 Diagnostic criteria for new symptoms induced by antipsychotic treatment New and rebound symptoms occur up to 6 weeks after drug discontinuation/dose reduction/switch, depending on the drug terminal plasma half-life (t1/2). New and rebound symptoms of CNS drugs have been reported to be more frequent and severe with short t1/2 and high-potency drugs [1,31,89,90]. New and rebound withdrawal symptoms are usually of short duration, persisting for a few hours to 2 weeks with complete recovery. However, if symptoms persist for more than 6 weeks, they become part of postwithdrawal disorders [41]. Fava et al. [91] proposed to replace the term discontinuation syndrome often used for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)/selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) [92] and antipsychotic medications [93] by “withdrawal.” CNS withdrawal occurs when the pharmacological effects of a drug diminish during medication discontinuation/dose reduction/switch, or in-between doses, which indicates an underlying pharmacological mechanism. The term discontinuation refers to the medical act of drug discontinuation or patient self-discontinuation. Furthermore, the term discontinuation is misleading since withdrawal symptoms may also occur with dose reduction or in-between doses for rapid-onset short-acting drugs. Examples include alprazolam and lorazepam, which can induce clock watching in-between doses, and clozapine which can induce late afternoon psychosis when given as a single dose at bedtime [41]. We will give criteria for each of the 3 types of withdrawal associated with antipsychotics [1,41,94]. New Symptoms New symptoms are the classic symptoms of withdrawal. They are not part of the patient's illness. New symptoms can be minor (anxiety, insomnia, and tremor) or major (seizures, psychosis, and death) [95]. Some are common to all CNS drugs, including narcotics, barbiturates, and alcohol, but each class of CNS drugs has its own specific new symptoms [1,41,90]. New symptoms common to CNS drugs include: nausea, headache, tremor, sleep disturbances, decreased concentration, anxiety, irritability, agitation, aggression, depression, or dysphoria [41], as listed in Tables 3 and 4. On the other hand, new drug-specific symptoms are linked to receptor binding affinities, and result from receptor supersensitivity which leads to increased neurotransmission due to removal of receptor blockade by antipsychotic treatment when medication is discontinued or switched, or dose is reduced [1,41,90]. New and rebound symptoms occurring during withdrawal and switch from and to SGAs (aripiprazole, asenapine, iloperidone, lurasidone, olanzapine, paliperidone, quetiapine, risperidone, sertindole, ziprasidone, and amisulpride) were reviewed recently by Cerovecki et al. [94]. In Tables 1 and 2, we integrate some of their findings on treatment-emergent symptoms related to removal of blockade or stimulation of dopamine and other receptors (serotonin, muscarinic, adrenergic, and histaminic receptors) by SGAs [94], and divide new antipsychotic-specific symptoms into: (1) serotonin withdrawal syndrome (equivalent to serotonin syndrome): flu-like symptoms, diarrhea, disorientation, coma, hyperreflexia, and stimulus-inducible clonus; (2) muscarinic withdrawal syndrome (also called cholinergic rebound syndrome): nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, hypothermia, increased salivation, tremor, parkinsonism, restlessness, and insomnia; (3) adrenergic withdrawal syndrome: increased blood pressure, headache, anxiety, agitation, increased heart rate, myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, palpitation, chest pain, presyncope, tremulousness, sweating, increased heart rate, myocardial infarction, hyperthermia, and fear; and (4) histaminic withdrawal syndrome: insomnia, agitation, tremulousness, increased seizure susceptibility, and amnesia (Table 2). Some new symptoms (Table 2) have been reported to occur more than 6 weeks after discontinuation: myocardial infarction and death after discontinuation of β-blockers [96]; hyperreflexia and inducible clonus after abrupt discontinuation of clozapine [97]; inducible seizure after discontinuation of chronic H1antihistamine treatment in rodents [98], and persistent insomnia following drug discontinuation/dose reduction of central muscarinic anticholinergics [1,90], and alcohol [95]. Table 3 Diagnostic criteria for rebound psychosis induced by antipsychotic treatment Table 4 Diagnostic criteria for persistent postwithdrawal supersensitivity psychosis induced by antipsychotic treatment Rebound Rebound Syndromes Associated with CNS Drugs The second type of CNS drug withdrawal consists of rebound symptoms (Tables 1, 2) [41]. It refers to a sudden return of patient symptoms above pretreatment levels and is usually short lasting. Rebound symptoms should be distinguished from pharmacological rebound, which produces both new and rebound symptoms. Pharmacological rebound is caused by a sudden increase or decrease in receptor-mediated effects due to removal of receptor blockade following drug discontinuation/dose reduction. This includes adrenergic rebound [99], cholinergic rebound [100,101], serotonin rebound [97], and histamine rebound [98]. We make a distinction between new and rebound symptoms, though they may have the same pharmacological mechanism [1,41,94]. The difference between new and rebound symptoms is whether present before treatment and known to the patient (rebound) or not present before treatment (new) and known to the patient. Cholinergic rebound produces both new symptoms: nausea, vomiting, salivation, abdominal cramp, diarrhea, hypothermia, tremor, insomnia, depression, and rebound symptoms listed in Tables 1 and 2; adrenergic rebound produces increase or “overshoot” in blood pressure and in heart rate above pretreatment and is also associated with new symptoms such as insomnia and anxiety [99,102]. Rebound anxiety and insomnia, seen with short-acting benzodiazepines [1], are also associated with new symptoms [103]. Withdrawal insomnia [104] and rebound insomnia [105] were identified as separate entities in all-night EEG recording studies. Recently, we reviewed CNS drug rebound syndromes [41]. Several CNS drug rebound syndromes have been reported to occur following drug discontinuation after short-term use: REM rebound with barbiturates and non-benzodiazepine hypnotics [106,107]; rebound myocardial angina and infarction with propranolol [108]; rebound insomnia [105], rebound anxiety [103], and rebound panic [109], with benzodiazepines with short and intermediate t1/2(triazolam, lorazepam, and alprazolam); and rebound depression [1,41]. Rebound depression has also been observed at a greater frequency with high-potency (paroxetine) and/or short-acting SSRIs and SNRIs [1,41]. In 2 double-blind placebo studies, patients with major depression had their maintenance paroxetine, sertraline, or fluoxetine treatment interrupted with placebo substitution and treatment reinstitution [110,111]. In one of the studies [110], patients taking paroxetine and sertraline had a sudden worsening of depressive symptoms upon drug discontinuation with a return to baseline depression measurements after reinstitution of the treatment. In both studies [110,111], patients taking fluoxetine did not have rebound depression, confirming that fluoxetine with a long t1/2 including norfluoxetine is less likely to cause rebound [41]. In contrast, patients treated with paroxetine had rebound depression in both studies [41,110,111]. The prevalence of high-dose use [112] is greater among patients taking benzodiazepines with short-intermediate t1/2 (e.g., triazolam, lorazepam, and alprazolam) than patients taking benzodiazepines (clonazepam, clobazam, and diazepam) with long t1/2; these differences persist even after 12-year long-term use [112]. Rebound syndromes respond rapidly to reinstitution of the offending drug, which often leads patients to false beliefs about efficacy and need for the drug [90]. The psychological belief of needing the drug for fear of having symptoms return appears the same for short-acting and short t1/2 CNS drugs, including antipsychotics (quetiapine) [1], paroxetine (SSRI) [41], lorazepam [103], alprazolam [112], cocaine [113], and heroin [114]. Rapid-onset drugs with short t1/2 will have an increased risk of rebound upon withdrawal, as illustrated by cocaine and heroin [114]. Rebound symptoms can be persistent in some patients, for example long-lasting insomnia after withdrawal from sustained alcohol abstinence [95] and rebound psychosis after long-term antipsychotic treatment [1,14]. Rebound Psychosis The proposed diagnostic criteria for rebound psychosis are given in Table 3. Rebound psychosis is defined by a rapid return above pretreatment levels of at least one positive symptom listed in the Rating Scale for Psychotic Symptoms (RSPS) [73,74]. Rebound psychosis lasts up to 6 weeks after peak onset (Table 1); if it persists longer, it becomes a postwithdrawal disorder, as for new symptoms persisting more than 6 weeks. Rebound psychosis is generally short lasting and considered as a reversible form of SP, equivalent to reversible withdrawal TD [1]. Any rebound symptom, such as an increase in blood pressure, myocardial infarction, insomnia, or psychosis, has the potential to become a persistent postwithdrawal disorder when lasting more than 6 weeks, often lasting several months and even years [1,41,95,96]. As with other CNS drugs (benzodiazepine, SSRI/SNRI, heroin, and cocaine), antipsychotics that are rapidly eliminated and/or that rapidly dissociate from the D2 receptor including clozapine (time to peak concentrations in plasma, tmax: 3-4 h; t1/2: 16 h [115]) and quetiapine [116] (tmax: 1-1.8 h; t1/2: 7 h [115]) have greater risks of rebound when medication is reduced, switched [59], or discontinued [1,33,39,40]. Patients on clozapine monotherapy taken as a single dose at bedtime report late afternoon return of symptoms [1]. For both the immediate-release formulation (IR) and the extended-release formulation (XR) of quetiapine, it is common in clinical practice to have difficulty in decreasing the drug dose, as it causes rebound anxiety and rebound insomnia (the drug possessing anxiolytic and hypnotic effects [117]), and later causes an in-between dose clock watching for return of symptoms, e.g., patient watches the clock to make sure the next dose is not missed for fear that symptoms might return, when given once a day above 150 mg [117] over a 2-month period [1,41]. The pharmacokinetics [118] and the central D2 receptor occupancy pharmacodynamics [119] of IR quetiapine given twice daily and XR quetiapine given once daily are similar [118,119]. Rebound psychosis with SGAs was first seen with clozapine [33] and then quetiapine monotherapy [39], but was later seen with all SGAs [34,35,36], with overt prevalence depending on drug t1/2 and potency. Quetiapine and clozapine have a particular D2 pharmacological profile compared to other SGAs: loose binding displaced rapidly from the D2 receptor [120], fast dissociation from the D2receptor [116], brief and weak action of clozapine on brain dopamine systems [116,121], and high transient initial D2 occupancy by quetiapine with minimal occupancy at the end of the dose interval [122]. This D2 profile of clozapine and quetiapine leads to differences in SP manifestations [1]: elevated incidence of rebound psychosis with clozapine [1,33,39,101], which is a reversible withdrawal subtype of SP [1], and severe drug tolerance with IR quetiapine given as antipsychotic monotherapy [39]. This might be explained by initially high D2 occupancy followed rapidly by low occupancy at the end of the dosing interval [122]. Postwithdrawal Disorders Postwithdrawal Disorders of CNS Drugs Postwithdrawal disorders have been described with all classes of CNS drugs [1,41]. Early recognition of postwithdrawal disorders for a given class of drugs is facilitated by the presence of high-potency drugs combined with short t1/2 [1,123,124]. Due to the short duration of action, there is a rapid decrease in occupancy of receptors produced in greater number by potent blocking drugs, thus resulting in a greater number of receptors in their unblocked state [1,108,123,124]; this was the case for β-adrenergic blocking drugs. As early as 1975, dose was highlighted as an additional factor for early recognition of postwithdrawal disorder; 160-320 mg propranolol/day would produce an adrenergic rebound unmasked rapidly by discontinuation, which led to an increase in cardiac contractibility, heart rate, myocardial ischemia, and rapid death, even after short-term use (6-12 weeks) [108]. Interestingly, in this first report of adrenergic rebound, major complications such as death were seen in patients who responded better to propranolol [108], which is also a characteristic of SP, most often seen in good antipsychotic drug responders [14,72]. Following abrupt withdrawal (even gradual withdrawal) of β-adrenergic drugs after long-term use, it was relatively easy to demonstrate an overshoot adrenergic rebound with pretreatment symptoms reappearing suddenly - increase in blood pressure, heart rate, myocardial infarction, headache, and anxiety above pretreatment levels [96,102]. The early recognition of supersensitivity rebound with β-adrenergic drugs helped to identify its underlying receptor supersensitivity mechanism through catecholamine stimulation by isoprenaline (isoproterenol), a nonselective β-adrenergic receptor agonist in patients [99,124,125], and later identify persistent postwithdrawal disorders consisting of an increased risk of myocardial infarction and mortality following their discontinuation [96]. Houston and Hodge [102], in their review of β-adrenergic blocker withdrawal syndromes, described 7 studies showing rebound and persistent withdrawal with 80 mg/day propranolol and a study showing these withdrawal syndromes after only 7 days of propranolol use. Doses below 80 mg propranolol/day appear safe to use in psychiatric clinical practice, but gradual dose reduction of low-dose propranolol is also recommended especially in patients at risks of myocardial infarction and essential hypertension. Rebound anxiety and insomnia were also first demonstrated with short-acting and potent benzodiazepines [90,103,105], and later as postwithdrawal disorders for alcohol [95] and benzodiazepines [104,126]. Other known postwithdrawal disorders are major depression and dysphoria in cocaine [113,114] and amphetamine withdrawal [114]. Within a drug class, specific drugs such as fluphenazine, perphenazine, quetiapine, clozapine, triazolam, and paroxetine permitted identification of new postwithdrawal disorders [1,33,39,41,109,127]. For SSRIs and SNRIs, several postwithdrawal disorders after long-term use have been described; interestingly, these postwithdrawal disorders consist of disorders that can be treated successfully by SSRIs and SNRIs, such as obsessive-compulsive, panic, generalized anxiety, and gambling disorders [1,41,109,127,128,129]. All these postwithdrawal disorders have been shown to occur more frequently with paroxetine [41,109,129,130]. This suggests that paroxetine should not be used anymore. For antipsychotics, two persistent postwithdrawal disorders, TD and SP, have been described [14,28,30,31,131]. When the symptoms last less than 6 weeks, they are considered as withdrawal dyskinesia and rebound, or withdrawal psychosis, respectively. When the symptoms last longer, they become postwithdrawal disorders, TD, or SP [1]. Discontinuation of short- and long-term β-blocker therapy can uncover long-lasting β-adrenergic supersensitivity [96,99]. Similarly, it has been known since the 1970s that long- and short-term dopamine receptor blockade by antipsychotics can both produce receptor supersensitivity [132]. The persistence of the dopamine supersensitivity syndrome depends on the duration of the preceding blockade [132] and on the specific antipsychotics used (fluphenazine, perphenazine, clozapine, and quetiapine) [1,41]. Similarly to β-adrenergic supersensitivity which may occur early and severely with β-blockers [108], TD can occur after short-term use (1 month) of chlorpromazine (FGA) in a patient with schizophrenia [133], and in a nonpsychiatric patient after a 4-month treatment with a gastric preparation containing trifluoperazine (FGA) and an anticholinergic drug [134] in an irreversible and extremely severe form. Supersensitivity Psychosis The proposed diagnostic criteria [14] for SP as a CNS postwithdrawal disorder [41] are presented in Table 4. The criteria take into account results from the 3 recent studies in patients treated with SGAs (n = 505) reviewed above [34,35,36], which examine the clinical characteristics of SP, 2 specifically focusing on TR schizophrenia (online suppl. Table 2). In addition, we took into account the results from the 2 studies by Fallon and Dursun [37 ]and Fallon et al. [38], which examined the link between SP and relapse in treatment-adherent schizophrenic patients without drug discontinuation who were not taking clozapine or quetiapine [37,38]. Exacerbation of psychosis by dopamine partial agonists was added as a risk factor (minor criterion) following the study by Takase et al. [36]. Vulnerability to minor life events was explicitly added to the minor criterion of exacerbation of psychosis by stress, following the results of Fallon and Dursun [37 ]and Fallon et al. [38]. Finally, the criteria define severe therapeutic drug tolerance more precisely as a nonresponse to doses equivalent to ≥600 mg chlorpromazine/day/12 mg haloperidol/day, when the patient has previously responded to lower doses. In addition, compared to 1991 criteria, major criteria define positive symptoms specifically [73,74]. Major criteria C2, C3, or C5 do not need minor criteria as was shown by the SP criteria used in the 3 recent Japanese studies of SP (n = 505), which included both patients with and without TR schizophrenia (online suppl. Table 2) [34,35,36], and in the 2 relapse studies [37,38]. Major criteria define rapid psychotic exacerbation or relapse upon drug discontinuation/dose reduction/switch of antipsychotics, and drug tolerance which refers to the lessening of drug therapeutic effects with continued treatment and the need for increasing doses to achieve the same beneficial effect. Minor criteria are risk factors for SP (Table 4); they help to identify patients at risk for SP relapse. One minor criterion is needed if only one of the major criteria present is C1, C2, or C6 (Table 4). We will now describe how SP criteria might be linked to an increase in D2/D2High receptor density. Pharmacological Link between a Compensatory Increase in D2/D2High Receptor Density and SP All antipsychotics, including the most recent SGAs [26], have the potential to produce D2upregulation. For instance, using laboratory animals, Tarazi et al. [135] reported upregulation of D2 receptors by olanzapine, risperidone, and quetiapine. Kusumi et al. [136] showed an increase in striatal D2 density following subchronic treatment with doses of chlorpromazine and perospirone (SGA) that produce therapeutic levels of striatal D2 receptor occupancy but not with low doses of chlorpromazine, risperidone, and olanzapine. While some antipsychotics may not elevate the density of D2 receptors, they can still raise the number of dopamine D2High receptors [25]. The increase in the number of D2 and/or D2High receptors enhances dopamine-mediated transmission [4] (Fig. 1). This may lead to more severe psychosis than seen in previous episodes during SP relapse or exacerbations, with new schizophrenic symptoms of greater severity such as disorganized behavior [14]. Patients with SP are more vulnerable to stress [14,69], minor life events, and daily hassles [14,37,38,69]. Stress increases dopamine levels in the brain [137]. In the presence of increased D2/D2High density, stress-induced dopamine in the extracellular space will produce greater D2-mediated signaling, leading to vulnerability to minor life events in patients with SP [14,69] even without drug discontinuation/dose reduction [37,38]. SP patients without drug discontinuation/dose reduction could be considered as having an overt form of SP [1,14]. As dopamine binds to D2receptors in competition with antipsychotic drugs, antipsychotics with less D2 receptor affinity allow more dopamine to bind to the receptors, and psychotic relapses due to SP will appear more rapidly. Another feature of SP is the gradual tolerance to the therapeutic effect of antipsychotic medications, where previously efficacious doses can no longer adequately control psychotic symptoms. Continuous D2 occupancy by antipsychotics, within or above the threshold for prolactin and movement disorders (i.e., in the 72-78% range [4,138]), increases D2 density as a compensatory reaction to reduced dopamine-mediated signaling. As D2 density increases, the therapeutic level of D2 occupancy (65%) [4,138] becomes higher [4], and previously efficacious doses are insufficient to suppress or cover psychotic symptoms. In order to improve psychotic symptoms, at least temporarily, higher doses are required [20], and therapeutic drug tolerance further develops. This has also been shown in animal models of antipsychotic-like efficacy, where continuous blockade of D2 receptors by antipsychotics, at clinically representative levels, produces tolerance to ongoing treatment, and higher doses can temporarily restore efficacy [9,10]. The optimal range of D2 occupancy in drug-naïve schizophrenia has been established [138], and theoretically determines the optimal dose range for antipsychotic drugs [4]. Therefore, patients who previously responded well to antipsychotics, but now have become poor responder or have histories of maintenance treatment with doses equivalent or higher than 600 mg chlorpromazine/day and 12 mg haloperidol/day are at increased risk for SP. Poor response to 2 antipsychotics at doses equivalent to or higher than 600 mg chlorpromazine/day is a criterion for TR schizophrenia [75,76]. Following antipsychotic discontinuation or sudden dose reduction, psychotic relapse develops more rapidly in patients with SP than in those without [69]. As the antipsychotic drug is eliminated with its specific t1/2, endogenous dopamine would now have access to a greater number of D2 and D2High receptors (Fig. 1), explaining why psychotic symptoms appear more rapidly in SP patients during drug discontinuation/dose reduction/switch of medication. However, the delay before the appearance of psychosis will also depend on the t1/2 of each drug. As optimal therapeutic D2 occupancy increases [4], increasing the antipsychotic dose would further mask TD [139] and SP [1], produce parkinsonism and negative symptoms, but also temporarily improve positive symptoms [4,34]. Some patients with severe SP who are also taking high doses of antipsychotics may exhibit all of these symptoms at the same time [1,34,140]. This mixed syndrome of drug-induced movement disorders and psychosis is temporally improved by giving the antipsychotic in divided doses [69]. Thus, SP may be masked, overt, or mixed [1], like TD [19]. The fact that SP can be overt during dose reduction, and masked by the causing drug during treatment [14,28,30], explains the therapeutic tolerance observed when antipsychotics can no longer mask psychotic symptoms at previously efficacious doses, and further increases in doses are necessary to obtain similar therapeutic effects [14,28,30]. Tolerance needs to be identified early to avoid increasing doses. Once therapeutic tolerance is identified, instead of dose increases to cover SP, strategies that we propose here should be considered, primarily the use of low doses of antiseizure drugs [1], the use of the minimal therapeutic dose of antipsychotic, and regular but intermittent dosing. Switching from one antipsychotic to another can potentially induce or uncover SP [14,37,69,94]. Switching antipsychotics will allow SP to emerge in patients either with or without a past history of SP [36]. This suggests that a medication switch can unmask SP induced by previous antipsychotic treatment, particularly in patients taking doses equivalent to ≥600 mg chlorpromazine/day/12 mg haloperidol/day. SP often occurs in the presence or history of drug-induced movement disorders, most often parkinsonism or TD [14,28,30,37]. This is expected since parkinsonism and other drug-induced movements are the best predictors for TD [1,71,81] and SP [1,37,38]. As striatal D2 occupancy by antipsychotics exceeds 65%, a clinical response is likely to appear, hyperprolactinemia when >72% and parkinsonism and movement disorders when >78% [138]. The therapeutic window of 65-72% D2 occupancy proposed by Kapur et al. [138] in their PET study of first-episode schizophrenia is relatively narrow and corresponds to doses >0.5 mg haloperidol/day [138]. Iyo et al. [4] suggested to extend the therapeutic window to >78%, i.e., when movement disorders appear, since movement disorders are easier to detect clinically and also because not all antipsychotics increase prolactin. Therefore, continuous D2 occupancy by antipsychotics above the narrow therapeutic window of 65-72% [138] or above the 72-78% threshold for prolactin/movement disorders may produce undetected parkinsonism and SP [1,4,19,28]. As already mentioned, Kapur et al. [138] found that the threshold level of striatal D2 receptor occupancy for movement disorders is >78% in first-episode schizophrenia. While catalepsy is seen in rats with doses that occupy >80% [141,142], dopamine supersensitivity can be seen at doses that occupy <80% [9,10,11,12]. Indeed, in animal models of dopamine supersensitivity, the doses we have studied occupy 73-74% of striatal D2receptors [9,10,11,12]. Table 5 Guidelines for the prevention of supersensitivity psychosis (SP) and tardive dyskinesia (TD) The second step (Table 5) is the administration of minimal therapeutic doses during maintenance treatment following the acute phase. The dose given in the acute phase is reduced gradually when initiating the maintenance treatment [148]. During the acute phase of psychosis, excessive dopamine release competes with antipsychotics for D2 receptor binding and depletes dopamine in the synaptic cleft [149], which creates a delay in reaching a new equilibrium. The third step (Table 5) is to keep D2 occupancy within the optimal therapeutic range while maintaining the minimal therapeutic dose. This must take into account the side effects and patient's tolerability, which could be predicted by 4 pharmacokinetic parameters (clearance, volume of distribution, t1/2, and bioavailability) [150]. In clinical practice, one should take into account that peak-to-trough plasma concentrations vary greatly and will depend on a number of variables. These include dosing interval and drug formulation [151], D2 receptor affinities, lipophilicity, active metabolites, patient characteristics (ethnicity and gender), concomitant medications, comorbid diseases, and general physical health [151,152]. While it is generally agreed that for oral SGAs (risperidone, olanzapine, clozapine, quetiapine, and ziprasidone) pharmacokinetic parameters are not sufficient for selection [115], selection of SGAs should be based on efficacy, side effects/tolerability, drug discontinuation-induced withdrawal symptoms and postwithdrawal disorders [1], and drug formulations [4,151]. For LA injectable antipsychotics, pharmacokinetic data in product monographs are of limited value for clinicians to choose the interval of administration [153]. In their recent review, Lee et al. [153] recommend using t1/2 for LA injectable SGAs to decide on the dosing interval in clinical practice. Continuous blockade of D2 receptors could contribute to the emergence of SP according to research conducted in animals. This work shows that when using the same achieved dose, peak level of D2 receptor occupancy, route, and duration of treatment, continuous antipsychotic treatment/D2 receptor blockade (as achieved via subcutaneous osmotic minipump) favors dopamine supersensitivity, while intermittent treatment/D2 receptor blockade (via daily subcutaneous injection) does not [9,11,154]. There are reports that intermittent antipsychotic administration via daily subcutaneous injection can produce dopamine supersensitivity [155,156,157,158]. However, the antipsychotic doses used are quite large and would produce excessively high and clinically unrepresentative levels of striatal D2 receptor blockade [159]. Continuous antipsychotic treatment could promote dopamine supersensitivity because it disrupts dopaminergic signaling unremittingly. This evokes compensatory changes including an increase in the number of striatal D2 and D2High receptors in the striatum (Fig. 1) [9,10,50]. In contrast, intermittent antipsychotic treatment allows at least some level of dopaminergic signaling to occur in between peaks in D2 receptor occupancy. This might be sufficient to prevent the brain changes that produce dopamine supersensitivity. The challenge is how to define “intermittent treatment” in clinical research and clinical practice. The clinician will often use short interdosing intervals (e.g., not taking antipsychotics on the weekends), to achieve minimal therapeutic dose [1]. In patients, there is likely a “break point” where if the antipsychotic dose/striatal D2 receptor occupancy has been low enough for long enough, the treatment might not be efficacious anymore to prevent relapses, thus being below the minimum therapeutic dosing. However, continuous dosing is not always necessary to maintain therapeutic efficacy. One prospective study by McCreadie et al. [160] indicates that intermittent administration with short interdosing intervals (as modeled in the animal studies described above [9,11,154]) can be as effective as continuous dosing in preventing psychotic relapse. In this double-blind study, patients were randomly assigned to either continue treatment with fluphenazine decanoate given every 2 weeks (continuous treatment, n = 18) or be switched to daily pimozide equivalent given 4 times a week (intermittent treatment, n = 16) [160]. Relapse rates over the next 9 months were similar in both groups. A second prospective study was a 6-month, double-blind, controlled trial in outpatients with schizophrenia stabilized for ≥3 months on oral antipsychotic given once daily [161]. The patients were randomly assigned to either treatment as usual (n = 18) or the same daily dose given orally every other day (n = 17; risperidone = 6, olanzapine = 11). Over the 6-month interval, symptom exacerbation and number of hospital admissions were similar in both groups. Thus, the 17 patients who had a 50% reduction in their maintenance dose given as alternate-day treatment (the “extended dosing” group) had similar relapse rates compared to those who kept taking their treatment as usual once a day [161]. However, reduction in the maintenance dose on one hand and continuous versus intermittent treatment on the other were confounded. To directly evaluate the effects of continuous versus intermittent antipsychotic treatment, a study would have to give the same “equivalent” dose daily versus every other day (e.g., 2 mg risperidone/day once daily versus 4 mg risperidone every other day). “Extended dosing” by giving treatment every other day is one strategy to reduce antipsychotic dose by 50%. The authors did not mention the length of prior antipsychotic treatment or the prior daily milligram dose of the 3 medications taken (risperidone, olanzapine, and loxapine). It is likely that the D2 occupancy was lower than the narrow therapeutic window of 65-72% found by Kapur et al. [138] for the acute/subacute phase and for first-episode schizophrenia. The McCreadie study [160] is more interesting in this respect since patients received a daily dose of oral pimozide 4 times a week (Monday to Thursday; intermittent dosing strategy), which was equivalent to the previous maintenance dose of LA injectable fluphenazine decanoate; intermittent continuous dosing strategy), thus testing the concept of intermittent antipsychotic treatment to achieve minimum therapeutic dosing and prevent dopamine supersensitivity. Similarly, Tsuboi et al. [162] conducted a single-blind, randomized, prospective, 1-year study including patients treated with oral olanzapine (n = 34) and oral risperidone (n = 34). Patients were stabilized for 6 months before entering the study. Patients were randomly assigned to receive either a treatment regimen producing continuous blockade of D2 >65% or a treatment regimen producing noncontinuous receptor blockade >65%. The continuous D2 blockade group had an estimated D2 occupancy >65% at trough and the noncontinuous blockade group had an estimated peak level of D2 occupancy >65% with an estimated trough level of <65%. The noncontinuous group had target doses of 7.1 mg olanzapine/day and 1.9 mg risperidone/day versus 10.4 and 3.4 mg/day for the continuous group, respectively, the latter producing >65% of estimated D2 occupancy. The authors did not find differences between both treatment regimens regarding the prevention of psychotic relapses. Again, here we have low- versus higher-dose maintenance treatment. However, the dosing interval of both drugs is not mentioned, and concomitant medications are not reported. The only information is “choice of dose at the discretion of the subject's physician on record.” Finally, we do not think that the study by Tsuboi et al. [162] is strictly a comparison of continuous versus noncontinuous but also low- versus high-dose treatment. In addition, a PET study by Nyberg et al. [163] showed that continuous D2 receptor blockade >65% was not necessary to prevent psychotic relapse. The study included 9 schizophrenic outpatients stabilized on haloperidol decanoate given intramuscularly every 4 weeks [163]. Despite an average fall of 52% in D2 receptor occupancy at the end of the injection interval compared to the occupancy level 1 week after injection, patients continued to be stable. Uchida and Suzuki [164] came to the same conclusion in their review of all PET and single photon emission tomography studies of LA injectable antipsychotics. They found that the CNS effects as measured by D2 receptor occupancy of LA injectable antipsychotics can persist for several months, and, as such, these medications may be administered at dosing intervals greater than those recommended in product monographs. The Uchida and Suzuki [164] review included a total of 14 studies with LA injectable FGAs (haloperidol decanoate, n = 11, and fluphenazine decanoate, n = 3), and 4 studies with LA injectable SGAs (LA injectable risperidone, n = 3, and LA injectable olanzapine pamoate, n = 1). Lee et al. [153] reached similar conclusions in their 2015 review of the pharmacokinetic data of LA injectable SGAs available in Canada and the USA (LA injectable aripiprazole, olanzapine, risperidone, and 1- and 3-month formulations of paliperidone palmitate). It should be noted that the clinical studies on intermittent or extended dosing cited here included small numbers of patients. Further clinical studies with larger samples are needed. In addition, future studies must also be designed so that minimal therapeutic dose and intermittent dosing are not confounded, thus allowing a dissociation of effects due to dose versus mode of administration. In summary, continuous occupancy of D2 receptors might not always be necessary to trigger the signaling cascades that underlie the antipsychotic effect. In parallel, the work reviewed here, including preclinical findings [9,11,154], also suggests that sustained antipsychotic treatment above the optimal D2 occupancy threshold for maintenance treatment (which appears lower than for acute and first-episode schizophrenia defined by Kapur [138]) could trigger changes that might be detrimental to the patient. This would include tolerance to therapeutic effects and SP. In parallel, work conducted in animals suggests that intermittent dosing would prevent dopamine supersensitivity [9,11,154]. Both the clinical and animal studies reviewed here suggest that an exploration of intermittent dosing strategies in patients is needed. LA injectable antipsychotics can also be given so as to produce intermittent dosing, taking into account the clinical recommendations of Lee et al. [153] and Uchida and Suzuki [164]. Intermittent dosing involves that D2 occupancy levels be high and then low, with each state maintained for approximately equivalent periods of time. Intermittent dosing should be one way to achieve the minimum therapeutic dose and prevent SP. Thus, LA injectable antipsychotics should not be increased rapidly to mask TD or SP except for palliative treatment in TR patients. However, one should avoid intermittent dosing defined as “targeted” antipsychotic treatment. This involves lengthy intervals without treatment and waiting for prodromal symptoms to reappear before restarting antipsychotic drug treatment. Such approaches were reviewed recently and they turned out to be disastrous for patients [161], since this “targeted” approach led to increased relapse episodes and poor outcomes. Instead, intermittent interval dosing, as used in our animal studies [9,11,154] and as explored in patients by Remington et al. [161], should be investigated further. This would involve intermittent antipsychotic administration with short interdosing intervals (e.g., for oral medication: weekends off and then treatment on Monday to Thursday, as in the McCreadie study [160]). Importantly, the interdosing interval must be long enough to permit peaks and troughs in brain levels of antipsychotic/D2 receptor occupancy. We predict that this enables some level of normal dopamine-mediated neurotransmission to occur in between peaks of D2 receptor blockade by antipsychotics, thus avoiding the neuroadaptations that lead to dopamine supersensitivity [165,166]. The interdosing interval to achieve peaks and troughs in antipsychotic brain levels will be a function of the t1/2 of the antipsychotic. For instance, the length of the interdosing interval would be longer for LA antipsychotics and comparatively shorter for short-acting antipsychotics. Finally, while threshold levels of D2occupancy have already been established for first-episode schizophrenia and acute treatment [138], they must still be established for maintenance treatment.- 3 replies

-

1

-

- antipsychotic

- neuroleptic

- (and 10 more)

-

In hindsight, I realize that I have been challenged most of my life with manic depression, little manic euphoria. I also now see the mental health issues which re-appear throughout my father's side of the family. Suddenly when I was in my mid 40's I started experiencing manic euphoric episodes.I was Baker Acted, mis-diagnosed, had another attack, hospitalized, forced to resign from a lucrative career that was the love of my life. In 2008 was diagnosed with bipolar disorder.( I have been at or below the poverty line since with the work I have been able to perform.) I was prescribed Zypreza and started a long depressed state, lethargic, and weight gain of at least 70 lbs. I was weaned off Zyprexa and have since been prescribed over different times drugs such as Celexa, Saphris, Artane, and Lamotrigine. As I was being taken off Zyprexa, my mood lifted, the weight started coming off but the movement disorder had already started in my face. Initially it was diagnosed by my doctor as tardive dyskinesia. The symptoms have continued to worsen to a now debilitating condition. As recent as yesterday, a new doctor, a neurologist thinks the condition is best defined , diagnosed as dystonia. In any event, the outlook is the same, no known cure. I never in a million years thought I would be so disabled and unable to provide for myself and others. But beside all these recent challenges, my weight is well managed, my spirits are good, my faith is strong. I know who I am. I just wish my body would cooperate!! I am going through the disability process now and as of the end of the month, I will lose my health insurance benefits through my last employer.

-

If you can walk, do it and count your blessings bc walking is a big deal

WiggleIt posted a topic in Symptoms and self-care

If you are able to walk, count your blessings. Regardless of if you are too depressed to walk or don't want to walk, please count your blessings if you're physically CAPABLE of walking. My movement disorder is so bad that if I walk more than a few steps, my legs buckle and my whole body starts to wiggle. I can only walk up and down the hallway of my house 3-5 times a day, maximum. Before meds, I used to be a runner, swimmer, bicyclist, dancer, figure skater, and weight lifter. The tricyclic antidepressants and benzo destroyed me so badly that now I can't even walk because I have lost control of my legs and arms. If I leave my house, my family pushes me in a wheelchair so that I don't flop everywhere in public. So if you are physically capable of walking, do it and be grateful, and while you are out walking to help yourself through WD, say a little prayer that one day I will be able to walk again, too. And if I ever am able to again, I will pray and think good things about you when I am walking. I know that it is hard for many people to exercise while in WD, but if you are able to walk, DO IT and count your blessings. It will only help your recovery.- 2 replies

-

- walking

- involuntary movement

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with: